johndoe@gmail.com

Are you sure you want to reset the form?

Your mail has been sent successfully

Are you sure you want to remove the alert?

Your session is about to expire! You will be logged out in

Do you wish to stay logged in?

Mrs Elizabeth Everest (1833–95) – the ‘Mrs’ was a courtesy title; she was unmarried – was hired as a nanny by Lord and Lady Randolph when Winston was only a few months old. She cared for the young Winston devotedly, alternately chivvying him and chastising him when necessary, listening tirelessly to his complaints of parental neglect and nursing him through various childhood ailments. He wasn’t always attentive or appreciative of her care and love. Here Mrs Everest writes to him just before his 17th birthday, “will you kindly favour me with a few lines, out of sight, out of mind with Winny”. She adds a “photo” of herself, drawn in ink at the bottom of the page.

Go to Document

“Winny” would later come to appreciate the contribution Mrs Everest – or “Woom” or “Woomany” as he called her – made to his life. When she was to be given the sack in 1893, he was horrified to see her treated so badly and her death only two years later, when he was twenty-one, caused him lasting grief. Here he writes to his mother, on the day of Mrs Everest’s death, that “I feel very low – and find that I never realized how much poor Old Woom was to me”. For many years he paid a local florist for the upkeep of her grave.

Go to Document

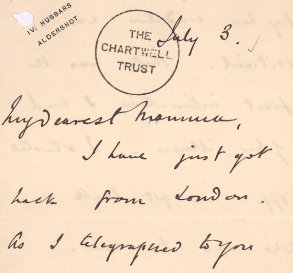

Lady Randolph Churchill had acute political acumen and was superbly charismatic and well connected. After the death of Lord Randolph Churchill, Winston suddenly found himself the focus of her interest and ambition and, in India and far removed from London literary and political life, he began to rely on her as his agent and ally. This was the age of the high society hostess, in which dinners and house parties were used to bring together influential decision-makers, and it was a role in which Lady Randolph excelled. Churchill now used his mother as a sounding board for his own developing ideas and pestered her to send him copies of the Annual Register (at great expense).

In this letter, written in 1897, he reveals much about his literary and political ambitions. He reports on writing “The Story of the Malakand Field Force”, and asks her to seek opinions of his essay "The Scaffolding of Rhetoric". He complains about the fact that his letters to the Daily Telegraph, which he had sent to his mother to forward on, had appeared unsigned, much against his wishes (“I had hoped some political advantage might be accrued”), and bemoans their publication with too many errors for too little reward.

Lady Randolph would continue to exert her influence and was ultimately instrumental in launching his political career, campaigning with him in the Oldham by-election of 1899 and the general election of 1900.

View Document

Churchill enjoyed the company of women, particularly when they demonstrated interest in him. He fell in love – and proposed marriage – to three women in his twenties: Muriel Wilson, the daughter of a wealthy shipowner; Pamela Plowden, the daughter of the British Resident in Hyderabad, and the actress Ethel Barrymore. It says much for his relationships with women that, while they each rejected his proposals, they remained his friends. At a dinner in March 1908, however, he sat next to Clementine Hozier, an earnest Liberal and a supporter of votes for women. Churchill was captivated. They became engaged after only a few months, in August 1908, and married at St Margaret’s, Westminster, on 12 September 1908.

Go to the document

Churchill had always maintained that he would not be "henpecked" into a decision on Votes for Women: “Nothing would induce me to vote for giving women the franchise. I am not going to be henpecked into a question of such importance”. This telegram of “hearty congratulations” on his engagement to Clementine from an anonymous Manchester suffragette (sometimes attributed to Emmeline Pankhurst) plays on his words.

Go to the document

Churchill, in his younger years, felt that women should not vote, writing in his copy of the 1874 Annual Register that they are “well represented by their fathers, brothers, and husbands”. Even when he voted in March 1904 in favour of a female suffrage bill, he was never more than a lukewarm supporter. (Under the then-current voting system, equal rights would only have enfranchised a minority of women (householders), most of whom were likely to vote Tory, so many Liberals were reluctant to endorse this type of reform.)

The logical solution – universal suffrage for both sexes – was a course to which Churchill was firmly opposed. Here, he responds to Prime Minister Asquith, when the latter first broached the possibility in November 1911, outlining his thoughts on women’s suffrage and its implications for the contemporary political landscape.

Go to the document

Like most women of her day, Clementine accepted that her own interests must always be subordinate to those of her husband but she supported him tirelessly. She helped him through a phase of black despair after he was sacked from the Admiralty and then resigned from government in 1915, having fallen from favour over the failure of the Dardanelles Campaign. She acted as his political agent in London while he was serving in the trenches on the western front.

In this letter, she writes to Winston, then at the front in France, of her dread of “coming home to find a telegram with terrible news” but she continues to offer advice and pass on details of her meetings with various leaders back in London, including the Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces, Lord French, telling him that to leave the front would “be injurious” to his reputation. In spite of her fears for his life, she finds herself “urging you not to leave the scene of these awful dangers”.

Go to the document

This is Winston Churchill at his most affectionate and domestic. After 1918, Clementine and Winston often holidayed apart and, on a cruise to the Far East in 1935, Clementine enjoyed a shipboard romance with Terence Philip, the director of the London branch of a New York art dealer. It was transitory and seemingly platonic but in any event Churchill seems not to have noticed. He wrote her a series of ‘Chartwell Bulletins’ in which he gave her the latest news of home, family and his collection of farm animals and pets. Here he tells her that “the guinea pigs have died ... How paltry you must consider these domestic tales of peaceful England compared to your dragons and tuartuaras”.

Go to the document

Winston Churchill's favourite holiday destination was the French Riviera, where he was able to enjoy the hospitality of wealthy American hostesses like Maxine Elliott, Consuelo Balsan and, post-’45, Wendy Reves, all of whom had a genuine affection for Churchill and played host to him in their villas, providing him with much-needed relaxation – and escape to the sunshine – during the inter-war years. Clementine, however, came to dislike the Riviera intensely, leaving Churchill to enjoy it without her.

Here Maxine writes to Winston, with a promise to send a car to meet him off the Blue Train in Cannes when he visits in the New Year: “the weather is heavenly here, and I am so looking forward to you coming on the 5th ... don’t let anything interfere with you coming”.

Go to the document

The other women in Churchill’s life were principally servants (those who kept house for Winston and Clemetine) and his private secretaries. Here, Churchill writes a reference in support of Grace Hamblin (1908-2002) – “entirely trustworthy in every respect” – who began as assistant to Violet Pearman, his private secretary, worked with Winston on his history of the life of the 1st Duke of Marlborough, and then graduated to become his private secretary and secretary to Clementine. She subsequently became the first administrator of Chartwell for the National Trust, after Churchill’s death, and was instrumental in ensuring that the Chartwell, now visited by thousands of people every year, is an accurate reflection of the house in its heyday.

While Churchill worked these other women in his life very hard, occasionally demanding that they stay up late into the night taking dictation, they generally regarded him with great affection, enjoying the excitement of working for a man who displayed such extremes of anger and kindness. And Churchill genuinely appreciated their help and support. After Violet Pearman’s death in 1941 (she was his secretary from 1929 to 1938), he paid £100 a year for seven years towards the cost of her daughter Rosemary’s education.

Go to the document

Women played only minor parts in Churchill’s political life. The one female politician in his own social circle was Asquith’s daughter, Violet Bonham Carter, a lifelong Liberal; although often at variance with Churchill, she supported his campaign against appeasement from 1936 to 1939.

Churchill also found an ally in Eleanor Rathbone, the MP and social reformer. She predicted in 1936 that only a truly national government led by Churchill and supported by Labour would stand up to the fascist dictators. Here, she writes to Churchill asking for a meeting to discuss a campaign in favour of collective security through the League of Nations, enclosing a cutting of her letter to the Manchester Guardian on the Government's European Policy. Later, Churchill would acknowledge her great skills in the House: “I was delighted at your dramatic intervention ... one of the most effective brief Parliamentary incursions into Debate that I have ever heard”.

Go to the document