johndoe@gmail.com

Are you sure you want to reset the form?

Your mail has been sent successfully

Are you sure you want to remove the alert?

Your session is about to expire! You will be logged out in

Do you wish to stay logged in?

Winston Churchill became Prime Minister of Great Britain in 1940, at a time of great international crisis, when dictatorship looked likely to triumph in Europe. Churchill used the power of words to boost morale, to rally resistance, to defy Hitler, and to build an alliance with the United States. His words had warned of the impending crisis. Now they helped keep Britain in the war and, by doing so, kept alive the possibility of the defeat of Nazism and the liberation of Europe. The exhibition, which ran from June through to September at the Morgan Library & Museum, shows how Churchill built and sustained his career by his mastery of the English language: through his many books and newspaper articles, his personal correspondence, his wit, and by the power of his oratory.

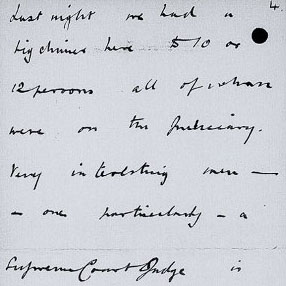

One of the earliest influences on Churchill’s oratory may have been his mother’s lover Bourke Cockran, the New York Democrat, in whose Fifth Avenue home Churchill stayed during his week-long first visit to Manhattan in November 1895.

Winston recorded his first impressions in this letter to his mother: “What an extraordinary people the Americans are! Their hospitality is a revelation to me and they make you feel at home and at ease in a way that I have never before experienced. On the other hand their press and their currency impress me very unfavourably.”

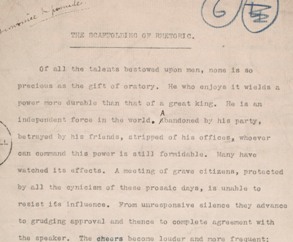

One of the earliest articles written by Churchill was this unpublished piece on public speaking called 'The Scaffolding of Rhetoric'.

In his draft typescript he commented on the variety of techniques that can enhance the speaker’s art, though at the time of writing in 1897 he had only made one major public speech, at Bath in England. He was also simultaneously engaged in writing both his novel Savrola and his first book The Malakand Field Force. This burst of literary activity set the scene for a career that would be underpinned by writing.

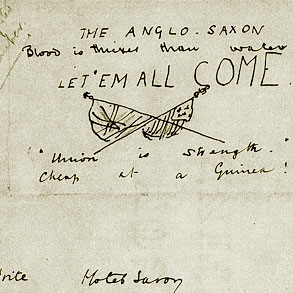

In March 1899 Churchill wrote to his mother from India about her plans to produce a new trans-Atlantic magazine, to be called The Anglo-Saxon Review.

The drawing at the end of this letter was deliberately mischievous, teasing her for going down-market, and in the accompanying letter he wrote, “Your title ‘The Anglo Saxon’ with its motto ‘Blood is thicker than water’ only needs the Union Jack & the Star Spangled Banner crossed on the cover to be suited to one of Harmsworth’s [a leading British newspaper owner] cheap Imperialist productions.” Interestingly, he also derided the “popular idea of the Anglo American alliance” as “that wild impossibility.” This was a view that he would change.

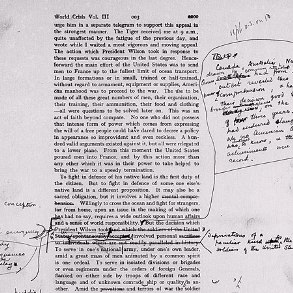

Churchill was a great supporter of United States intervention in the First World War. In the third volume of his history of the conflict, The World Crisis, published in 1927, he praised the “sense of world responsibility” shown by the United States in fighting “in defence of some one else’s native land.”

His original text had been even more effusive but, as this proof reveals, he toned down his pro-American sentiment. His additions might suggest this was done to avoid offending Canada, Australia and New Zealand, as he has added a note about their sacrifice. The document shows how meticulously Churchill reworked and refined his prose prior to publication.

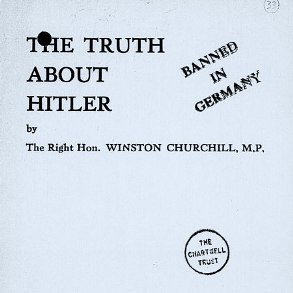

"It is not possible to form a just judgement of a public figure who has attained the enormous dimensions of Adolf Hitler until his life work as a whole is before us.” Throughout almost all of the 1930s Churchill was out of office, and in need of both money and a platform.

He wrote extensively on international affairs, and came to see a revived militaristic Germany as the greatest threat to Britain and Europe. He shared the horror of many at the brutality of the regime, and at its treatment of the Jews, but he did not see war as inevitable. In this article, first published in The Strand Magazine in November 1935 and later in abridged form in his book Great Contemporaries (1939), he made it clear that Hitler had a choice. Yet as the cover of the displayed pamphlet version shows, his words were to be “Banned in Germany.”

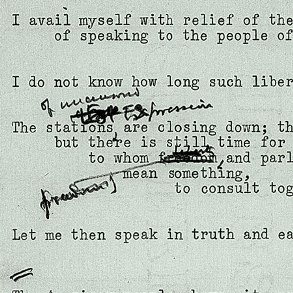

“They [the dictators] are afraid of words and thoughts: words spoken abroad, thoughts stirring at home – all the more powerful because forbidden – terrify them.” On 16 October 1938, Churchill broadcast directly to the United States.

The Munich Crisis had just ended with Germany being allowed to occupy part of Czechoslovakia. His message was simple. America could no longer afford to ignore what was happening in Europe, and there was still time to stand together and defend democracy against dictatorship. The speech contained a wonderful articulation of the power of words, but received a mixed response. Mr J Peckell Nathan wrote from Los Angeles to support Churchill, while New Yorker George Bailey, a veteran of the First World War, disagreed.

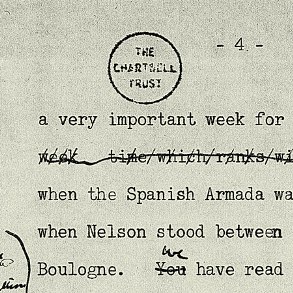

“We have read about all this in the history books; but what is happening now is on a far greater scale, and of far more consequence to the life and future of the world and its civilization, than those brave old times of the past." Churchill’s reputation as a war leader and as an orator was established by his broadcasts during the summer and autumn of 1940.

His response to the ‘blitz’ bombing of London, which began on September 7, was to invoke British history in order to send a personal message of defiance to Hitler. His draft typescript reveals how carefully he chose his words and refined his phrases. Times were desperate − 43,000 British civilians were killed during the Blitz − and the impact of Churchill’s words was hugely significant.

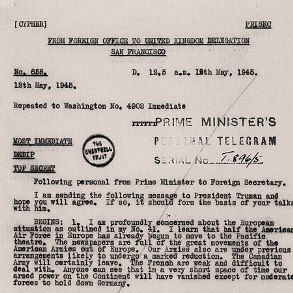

The closing stages of the Second World War led Churchill to the grim realisation that European stability might not be secured by the defeat of Nazi Germany.

In this telegram to British Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, also sent to President Truman, he expressed his concerns about American withdrawal from the continent and Soviet advance. He also used the term “iron curtain” to describe the new Russian front: a phrase that he did not formulate himself but which he was to popularise ten months later in a speech in Fulton, Missouri.

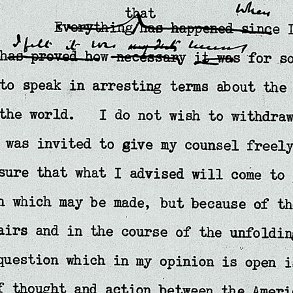

I do not wish to withdraw or modify a single word.” Speaking at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York just ten days after his famous 'Iron Curtain' speech, Churchill was forced to defend the remarks he had made in Fulton, Missouri, against criticisms that he was attacking America’s Soviet ally and promoting an ongoing alliance with Britain. Though controversial at the time, with the onset of the Cold War his words soon came to be seen as a prophecy.

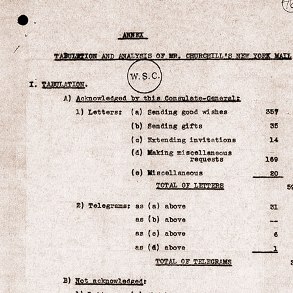

The British Consulate monitored Churchill’s New York mail and prepared this summary. While there is no doubting that Churchill was extremely popular with New Yorkers, there was still clearly a vocal minority opposed to him and his policies.