Are you sure you want to reset the form?

Your mail has been sent successfully

Are you sure you want to remove the alert?

Your session is about to expire! You will be logged out in

Do you wish to stay logged in?

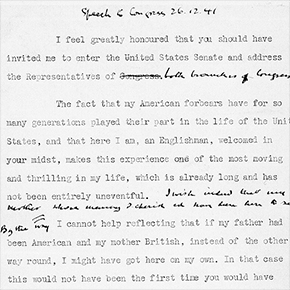

On Boxing Day 1941, less than three weeks after the Japanese military strike on Pearl Harbor, Churchill delivered this speech to the Joint Session of Congress. Referring to his American ancestry (on his mother’s side), his democratic convictions and observations of ‘an Olympian fortitude’ in Washington, he focuses on the parallels and similarities between the United States and Britain: their shared language, similar ideals and their now joint efforts for ‘the successful prosecution of the war’. The purpose of his visit is to begin mapping out their military plans in the wake of the United States’ declaration of war.

➜ Go to Document

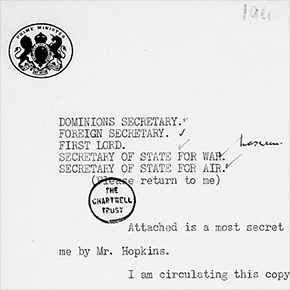

Marked ‘most secret’, this memorandum on Operations in Western Europe came from Roosevelt to Churchill via Harry Hopkins (special advisor to the President) proposing joint policy and invasion plans for 1942. Sent to a small handful of high-level British ministers, who were instructed to open and read it personally, this memorandum served as the starting point for what later become known as Operation Overlord, and began with D-Day.

➜ Go to Document

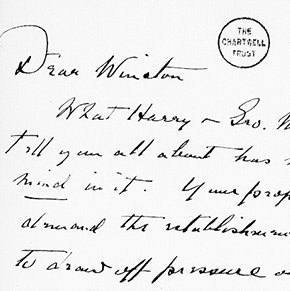

The special relationship between the Unites States and Britain during the war was helped greatly by the mutual respect and connection between Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt, President of the United States. This letter from Roosevelt to Churchill on 3rd April 1942 pledges a joint offensive and the establishment of a front in Western Europe. Delivered with a further message to Churchill from Harry Hopkins (Special Advisor and assistant to Roosevelt) and General George Marshall (Chief of Staff, United States Army), Roosevelt emphasises that this plan ‘has his heart and mind’.

➜ Go to Document

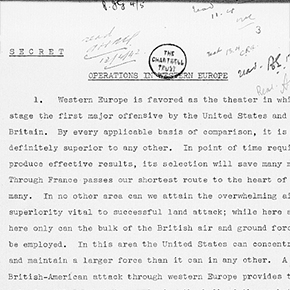

As early as April 1942, this report identified Western Europe as the preferred ‘theatre in which to stage the first major offensive by the US and Great Britain’. As the shortest route to the heart of Germany, General Marshall urges the British and US leaders to make decisions quickly in order to prepare for the attack and calculate an approximate date for a major offensive of approximately 5,800 combat airplanes and 48 divisions. Western Europe offers the ‘only feasible method for employing the bulk of the combat power of the United States, the United Kingdom and Russia in a concerted effort against a single enemy’.

➜ Go to Document

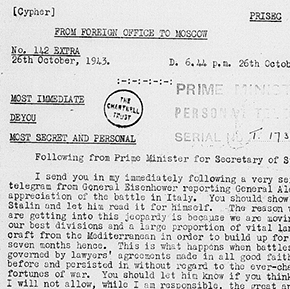

As the war progressed, resources became ever more stretched. In this telegram to Anthony Eden, Churchill is clearly concerned about the effect that preparations for Operation Overlord are having on Britain’s other theatres of war. Asking Eden to share a report from General Eisenhower on the situation in Italy with Stalin, he is uneasy about moving so many forces away from the Italian front in anticipation of Operation Overlord as it may jeopardise the Italian campaign. Churchill clearly states that while they will ‘do our very best for Overlord’ he is not prepared to suffer defeat in Italy to do so, and concludes that Overlord may need to be postponed.

➜ Go to Document

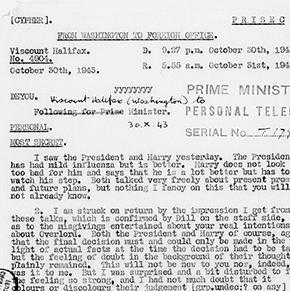

The joint offensive between Britain and the United States was a complicated arrangement, and despite the personal connection between Churchill and Roosevelt, misgivings inevitably came about from both sides of the Atlantic as to the other’s intentions. This telegram from Lord Halifax, British Ambassador to the United States, to Churchill reports on a recent meeting with President Roosevelt and Harry Hopkins. Halifax describes some misgivings in the United States about Churchill’s real intentions about Overlord.

➜ Go to Document

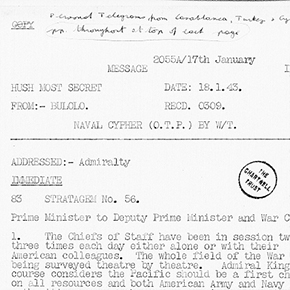

In January 1943, Churchill attended the Casablanca Conference in French Morocco, held to plan the Allied European strategy for the next phase of the war. Also in attendance were President Roosevelt of the US, General Charles de Gaulle and Henri Giraud of France, while Stalin had declined to attend due to the ongoing Battle of Stalingrad which required his presence in the Soviet Union. In this telegram from the conference to Clement Atlee, Anthony Eden and the War Cabinet, Churchill reports on progress, remarks on the different priorities of the delegates in the Mediterranean and Pacific, and expresses satisfaction with the result of discussions between Generals Alexander and Eisenhower. The result of the Casablanca conference was the unified statement of purpose that the Allies would accept nothing less than the ‘unconditional surrender’ of the Axis powers.

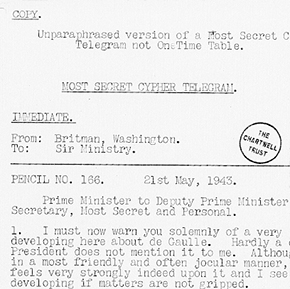

This telegram, sent from Churchill to Clement Attlee and Anthony Eden in May 1943, focuses on the character of General de Gaulle of France. Written with a sense of urgency and outrage, Churchill accuses de Gaulle of being Anglophobic, claims he is absorbed in his own personal career, and expresses concern that he is causing an estrangement between Britain and the United Sates governments. He urges the deputy prime minister and foreign secretary to bring this information before the cabinet, eliminate de Gaulle as a political force and bring the issue before Parliament. He makes it clear that he is in favour of informing the French Committee of National Liberation that Britain will have no further relations with them as long as de Gaulle is part of their assembly.

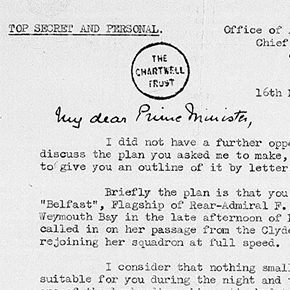

A letter written in May 1944 from Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay to Churchill, informing him of the arrangements that have been made for him to accompany the troops during the D-Day landings. Reassuring Churchill that he has not informed the First Sea Lord as requested, he has however mentioned the plan to General Eisenhower. Both Eisenhower and Ramsay are averse to the plan, and instead suggest Churchill delays his visit across the channel once the situation has been stabilised, because ‘you mean so much to the nation at this stage in the war that…any risk to your life…should not be taken unnecessarily’.

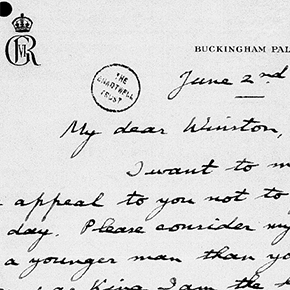

Written by King George VI in his own hand and dated 2nd June 1944, four days before D-Day, this letter appeals to Churchill not to accompany the troops despite his evident wish to do so. While he understands Churchill’s request to go, the King points out that he would see very little, would run a considerable and unnecessary risk, would be inaccessible at a critical time and his presence would be a considerable extra responsibility for the Admiral and Captain. He implores him not to ‘let your own personal wishes, which I very well understand, lead you to defeat from your own high standard of duty to the state’.

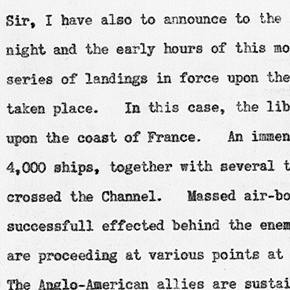

In this statement, Churchill announces to the House that in the early hours of that morning the first D-Day landings were successfully executed on the coast of France. Consisting of a monumental 4,000 ships, several thousand smaller boats and 11,000 aircraft, commanders report that everything is thus far proceeding to plan. While Churchill is cautious about the course of the war, he reports that they already believe actual tactical surprise has been achieved. With complete confidence in the Supreme Commander General Eisenhower and unity throughout the British and American Armies, he notes the troops’ high spirit is ‘splendid to witness’.

In this speech to the House of Commons, Churchill gave a heartfelt tribute to the late Roosevelt’s achievements as the leader of the United States both during the war and in peacetime. Churchill clearly held the President in great esteem, declaring him to be ‘the greatest American friend we have ever known, and the greatest champion of freedom who has ever brought help and comfort from the New World to the Old’. Thought of as one of the best Presidents of the United States to this day, and an icon of the twentieth century, Roosevelt’s ‘lustre’ is indeed still ‘discernible among men’, as Churchill predicted.