Are you sure you want to reset the form?

Your mail has been sent successfully

Are you sure you want to remove the alert?

Your session is about to expire! You will be logged out in

Do you wish to stay logged in?

Winston Churchill is best known for the vital role he played in the Second World War and his involvement in guiding Britain and the Allies to victory over Germany between 1940 and 1945. However, he also played his part in earlier wars.

Churchill’s first experience of war was as a twenty-two year-old, when he fought for Queen and Country in an outpost of the British Empire, on the North-West Frontier bordering Afghanistan. Although he risked life and limb as a young man, it was in the First World War (1914-18) that he perhaps took most risks, both personal and political. This war was to see both his humiliation and fall from grace – and, finally, his redemption.

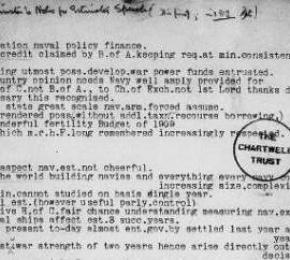

Churchill’s contribution to the First World War began back in 1911, three years before its start, when, as a thrusting young British minister, he was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty with full charge of the Navy. Deteriorating relations between France and Germany and the rapid expansion of the German Navy had prompted great anxiety in Britain. Churchill felt strongly that Germany wanted a great navy for “malignant design”. Although earlier he’d argued that Britain should cut back Britain’s own naval expansion, he now felt the country should be in “constant and instant readiness for war”. Thanks to Churchill’s energy and persistence, the fleet was indeed ready when war came.

Go to Document

The onset of the First World War in August 1914 put Churchill centre stage in an international crisis, a role for which he felt he was more than ready. Eager to emulate the deeds of his ancestor, the Duke of Marlborough, and believing he was destined to achieve greatness, Churchill felt anticipation and excitement – and the promise of glories to come – as the prospect of war became unavoidable.

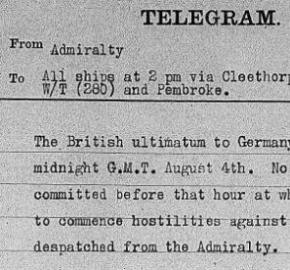

When Britain’s ultimatum to Germany to respect Belgium’s neutrality was ignored, Britain felt impelled to go to war. As First Lord of the Admiralty, Churchill issued the order to the Navy to "commence hostilities".

The war was to destroy the social order – and the world – in which Churchill grew up and, although he had no inkling of this at this stage, also any immediate ambitions to fulfil his destiny and achieve glory.

Go to Document

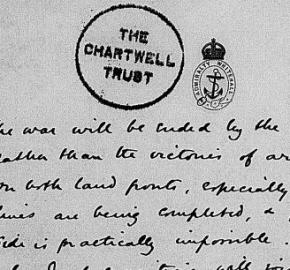

In December 1914, at the age of forty , Churchill was eager not just to run the Navy but to manage the war itself. As the conflict in Europe degenerated into stalemate, he became convinced that the only way to break the deadlock and end the war quickly was to mount a huge attack on Turkey through the Dardanelles Straits, in an attempt to knock Germany’s eastern allies out of the war.

Demonstrating his usual self-confidence, drive and determination, Churchill argues it would "be better to engage Germany on new frontiers … Naval command of the Baltic must be secured".

Go to Document

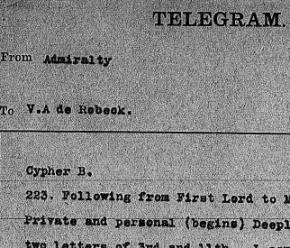

Churchill’s zeal and enthusiasm swept many anxieties aside and the high-risk offensive operation went ahead. It soon became clear that the planning of the operation was beyond the capabilities of the British leaders who had no system in place for effective combined operations. The Dardanelles Straits were heavily mined, the Navy’s ships were running against a strong current and were being attacked on all sides by the Turkish guns. Churchill continued to encourage the Navy to persevere. Writing to his brother, Jack, who was with the forces in the Dardanelles, he says “the vital thing is not to break off because of losses but to persevere. This is the hour in the World's history for a fine feat of arms and the results of victory will amply justify the price”.

Go to the document

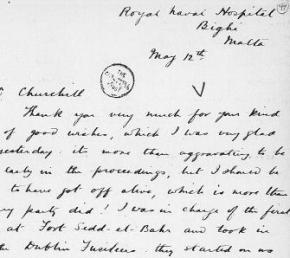

It was not to be. When it became clear the Dardanelles could not be forced using ships alone, it was decided (against Churchill’s wishes, as later became apparent) to land Allied troops on the Gallipoli peninsula. Turkish resistance was far heavier than expected and the expeditionary force, principally made up of Australian, New Zealand and British men, soon became trapped. The situation deteriorated into chaos and disaster. The human cost of the campaign was enormous. This first-hand account of the Gallipoli landings by Captain Neston Diggle left Churchill in no doubt as to the immensity of the losses. The mass slaughter of Allied troops led to Churchill’s fall into disgrace and humiliation and cost him his job.

Go to Document

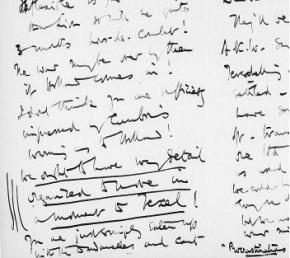

In Churchill's defence, complex decision making was behind the failure at Gallipoli. Prime Minister Asquith, Lord Kitchener, “Jackie” Fisher, as well as many at the War Council and War Office, all contributed to the plan and its failure. The elderly First Sea Lord Admiral Fisher, who had been a close friend of Churchill, frequently disagreed with Churchill on strategic issues. This prophecy by Fisher that the Dardanelles would be their “grave” was proved correct. Churchill fought back a few days after receiving this, quoting Napoleon: “We are defeated at sea because our admirals have learned – where I know not – that war can be made without running risks”. The risks proved too great.

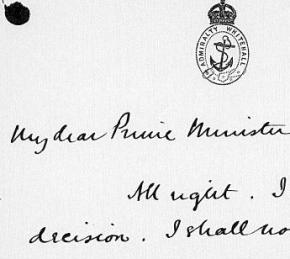

The deterioration in their relationship became evident when, on the Admiral’s resignation in May 1915 following the failure, he demanded that Churchill be ousted too. Although this didn’t happen immediately, the damage to Asquith’s Government had been done and Churchill was unceremoniously sacked.

Go to the document

While Churchill accepted the relatively lowly government position, he became increasingly disillusioned and despairing. He found it difficult to sit by and watch others fight the battle, seeing his own chances for glory pass him by. He felt “like a sea-beast fished up from the depths, or a diver too suddenly hoisted”; his “veins threatened to burst from the fall in pressure”. He retired to the country, to Hoe Farm, with Clementine and the children, and took up painting to fill the void.

However, demonstrating an ability that would stand him in good stead in years to come – the ability to recover from devastating blows – and finally unable to bear political impotence any longer, he resigned from the Government in November 1915. Churchill was forsaking the House of Commons for the trenches of Flanders.

Go to the document

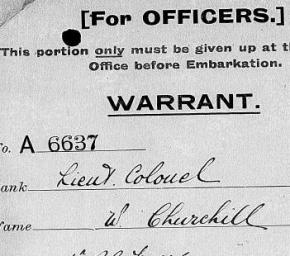

Churchill had hoped for an appointment as brigade commander but had to settle instead for command of a battalion. After a few weeks as a Major with the 2nd Battalion, Grenadier Guards, in January 1916 he was appointed Lieutenant-Colonel, commanding the 6th Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers.

Despite his inexperience and eccentricities as a commander, he gradually earned the respect of his men. In the tedium, chaos and danger of the trenches at “Plug Street” (Ploegsteert), he became a focussed and sympathetic leader and took considerable satisfaction in his new role. Here he writes to his mother that “I am happy here … I always get on with soldiers. I do not certainly regret the step I took … I know that I am doing the right thing out here … Do you know I am quite young again?”

Go to the document

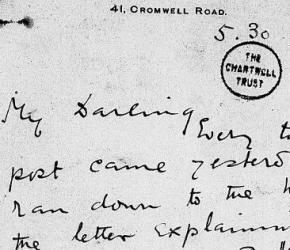

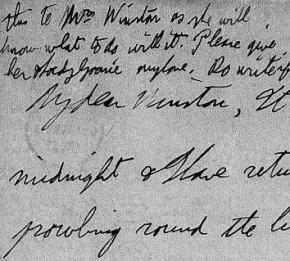

Like many wives left at home, Clementine felt keenly the loss of her husband and she wrote to Churchill almost daily, to which he always replied in kind. Her letters sustained and supported him, not only with tender words of love, but with advice, too. While she wrote to him with family news and of her own war work (organising canteens for munitions workers), she was also Churchill’s eyes and ears back in London, and kept in touch with his peers and contemporaries in political circles on his behalf. Although she dreaded “coming home to find a telegram with terrible news”, she knew that he had taken up active service in an attempt to rehabilitate his political reputation. To leave the front would “be injurious” to his reputation. In spite of her fears for his life, she finds herself “urging you not to leave the scene of these awful dangers”.

Go to the document

When his battalion was amalgamated with another, rendering his command redundant, he returned to London, honour intact. Fortified by a sense of purpose, he resumed political battles at home. Flanders had schooled Churchill in the realities of trench war and he returned to the Commons to give a soldier’s eye view of the conflict but, isolated on the opposition benches and facing the Liberal-Conservative coalition, his words went largely unheeded. While Haig and the generals were committed to a war of attrition by men, Churchill strongly believed in attrition by metal and machines.

Go to the document

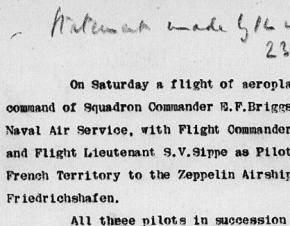

One particular machine excited Churchill greatly. The advent of powered flight several years earlier had inspired him to learn to fly himself (rather unsuccessfully). But it was as a military instrument that he championed the aeroplane. Although he had taken part in the last major cavalry charge in British history at Omdurman, he was keen to explore and exploit science in warfare. At his urging, the Royal Naval Air Service was formed in the spring of 1914. In the autumn of that year, Churchill, concerned about the role that German airships would play in bombing the British fleet, had approved what were to be the first of many bombing raids against Germany, on their Zeppelin sheds and repair facilities.

Go to the document

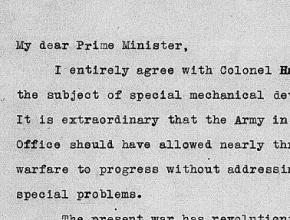

Early in the war, Churchill had also seen the value of mobile armoured vehicles. Along with his belief in the great importance of airpower as an instrument of war, Churchill had a passionate belief in the development of the land "Battleship". While at the Admiralty, Churchill had approved research into a new weapon that could cross trenches and barbed wire at a time when the War Office were still thinking of sending men to war on horseback. In January 1915, Churchill had written to Prime Minister Asquith that the war had changed all ideas about modern warfare. The key problem was “getting across … 100 or 200 yards of open space and wire entanglements”; horses – and men – could not negotiate this “no-man’s land” without massive losses. The land Battleship – what was to later become the tank – was born. And he was shortly to have the opportunity to put these "battleships" to the test.

Go to the document

Churchill’s desire to play a more important role in the war was eventually fulfilled when David Lloyd George toppled Asquith to become Prime Minister. In July 1917, German attacks on food supplies were threatening Britain’s ability to win the war and, with the positive findings of the Dardanelles Commission largely exonerating Churchill of responsibility for the disaster, Lloyd George took the risk of reintroducing him into Government. He appointed Churchill Minister of Munitions, putting him in charge of forging the weapons of war.

In August 1918, when the German offensive had burnt itself out, the Allies launched a surprise counter-offensive at Amiens, with a mass of Churchill’s "battleships" – or tanks – spearheading the attack. The modern machines of war – and Churchill – took their share of the battle honours. He had finally achieved some measure of the glory he had longed for.

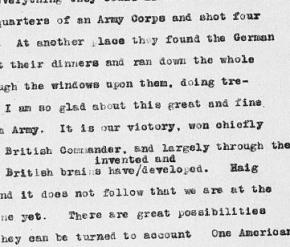

Here he writes to Clementine with quiet satisfaction at his achievements: “It is our victory, won … largely through the Invincible tank”.

Go to the document

While the last year of the First World War had finally seen Churchill restored to a position of some power and influence, the war years were, for him, a period of lost opportunity. Personally, he felt he had been unable to bring all his powers to bear in the struggle and, politically, he ended the war in a weaker position than that in which he had started it.

Churchill’s second in command on the Front (Archibald Sinclair, later Secretary of State for Air in the Second World War) wrote on Churchill’s return to London in 1916 that “I have never ceased to think of you playing a great perhaps the great part in this tremendous crisis”. Churchill had learnt many bitter lessons in the First World War – both personal and political – and he was to play that “great part” in another “tremendous crisis” when, steeled by his experiences, and wiser, he lead Britain to victory in another war.

Go to the document